A piece of rail hanging on a post was the camp bell, which set the rhythm of the day in the camp. At 4:30 a.m., the camp guard came up and pounded on it with a truncheon. Everyone who woke up was aware from the first seconds that this day could be their last in this world. Paradoxically, people did not know whether to be happy about it or not.

See it for yourself

While in picturesque Krakow, visit Auschwitz and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. Take advantage of KrakowDirect‘s organized tours and learn about the history of the largest death camp in history with a guide.

Choosing the organized tour option, you will have comfortable transport, tickets included in the price of the tour as well as a knowledgeable guide.

If you want to get from Krakow to Auschwitz on your own, you can use public transportation, train, or drive your car. The town is only 60 km west of Krakow.

Every day is a struggle for survival

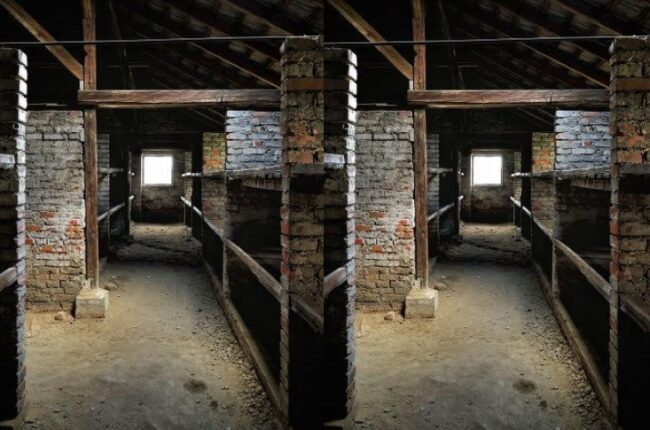

Thousands of people in the blocks of flats were forced to immediately get up from their bunks, haylofts or floors covered with straw. If you were late, even for a few seconds, you could be immediately beaten by the block leader with a truncheon.

Prisoners had only a few minutes to “wash” in the block washroom or use the latrine. Many simply did not manage to get to them. Then, also on the run and under pressure, they lined up for breakfast, if you could call it that. This was half a liter of tea or coffee-under camp conditions, these names meant water with an addition of coffee or a decoction of herbs.

There was no mention of a piece of bread or milk soup. The next gong called for the prisoners to line up in tens for morning roll call. Here was the order to form work squads. There was a real competition to get a job that was as light as possible.

Who could work, could live

Work in the kitchen or workshop, or more precisely, under a roof, was most favorable. Jobs such as carrying railroad sleepers or standing up to one’s waist in water and mud while clearing fishponds were avoided like the plague.

In the long run, they led people straight to a grueling death. Not surprisingly, people tried to find lighter work through the appropriate channels at the camp employment office.

Some tried to hide in the hospital block after the morning roll call. Medicine was scarce there and there was an unbearable stench and overcrowding, but it was still a better option than trying to hide in the block. Being temporarily unable to work meant a moment of respite for the prisoner.

One day of work in Auschwitz

The workday in the camp started at 6 am and lasted until 5 pm, with a half-hour “lunch” break around noon. Even more difficult was the work of those who were sent to work outside the camp. Sometimes they set out even before morning roll call and had to walk up to 10 kilometers!

From the point of view of the torturers, work, even the most senseless work like digging and filling in ditches, not only regulated the order of the day in the camp but was the prisoners’ only reason for existence. Only those who could work could live, and vice versa.

This did not apply only to the new arrivals, who were just learning how to work in the camp during the so-called quarantine. It was a torment, both in the summer heat and in the winter: running from place to place, “frog jumping,” climbing trees… Anyone who could not stand it was beaten until they were unconscious, or even to death.

Work commonly called entertainment

One of the permanent torments in the early years of the camp’s existence was singing national songs, in German of course, on the way to and from the worksite. The Nazis’ fondness for this ritual waned after the defeat at Stalingrad. There was even a ban on singing.

Coffee in the morning, coffee in the evening, and hunger for dinner

Hunger was an everyday occurrence. The combination of a camp diet and exhausting work was a mechanism designed to destroy the prisoner sooner or later. The camp soup served for dinner was simply lurked soup with swede, potatoes, and sometimes groats. Only those who had already experienced the killing hunger ate it without disgust.

The camp bread that was given out for dinner (the ration was about 25-30 dkg) was most often moldy and contained the remains of sawdust. There was no protein, fats, or vitamins in the camp diet. It was not until 1942 that prisoners could receive packages.

With meals so scarce and meager, food had to be “organized” in various ways to keep oneself or someone else alive. On the black market in the camps, onion or garlic was worth more than a 20-dollar coin. Not surprisingly, food and clean water, which were often unavailable for drinking or washing, often appeared in prisoners’ dreams.

Diseases, epidemics, and lack of hygiene

Ubiquitous lice and fleas, running rats, cold and damp. On top of that, it was so cramped that you could only sleep on your side. If someone got up to go to the latrine, when he returned, he had no place to sleep.

And if a prisoner found himself on a bunk under someone who had diarrhea, the night promised to be a nightmare. But not sleeping at night meant sleepiness and lack of concentration during the day, and most importantly: it weakened vigilance. Vigilance was essential for survival-from as early as 4:30 a.m. when the gong announced the start of the next ordinary day in the hell of Auschwitz.